The .44 Smith and Wesson Special

edited by John Dunn

Click on any thumbnail image for a larger photo.

The .44 Special descends from one of the very first center-fire revolver cartridges. Upon its introduction in 1907, it became one of the last of the cartridges designed for loading with black powder. It continues to thrive in the early 21st Century, having picked up quite a legacy for itself along the way.

That first cartridge, the .44 Smith and Wesson American, came with the introduction of Smith &Wesson’s first large caliber break-top revolver. With a 215 grain case-diameter healed bullet driven to 650 fps, it gained immediate acceptance as a weapon system adequate for use on the Western frontier. If historic factology is correct, Buffalo Bill Cody and Grand Duke Alexi of Russia successfully used the American to down bison from horseback leading directly to the development of the .44 Russian revolver and cartridge not long after 1870.

The .44 Special arrived on the scene with a number of performance expectations already in place. It was the immediate successor to the exceptionally accurate Russian. Such late century marksmen as the Bennett brothers and Ira Paine set records with the round and it was highly regarded by contemporary shooters. Apparently Smith &Wesson did not want this apple to fall far from the tree. The Special cartridge duplicated exactly the 246-grain bullet loading with a claimed velocity of 770 fps. The original black powder loading of the Special did succeed very handily in the accuracy department and the cartridge gained a lasting reputation as one of the most accurate of the large revolver rounds. Writer Mike Venturino attributes much of the reputation of the .44 Special to the extremely well engineered New Century Triple Lock revolver of 1907-15 rather than to any magical qualities in the round itself. As most revolver enthusiasts are aware, Elmer Keith found the thicker chamber walls of the Special revolvers less prone to catastrophic failure than the .45 Colt and used the cartridge as a basis for powerful game shooting loads.

As with the 45 Colt and 38 Special, measured velocities of the generic factory load fall short of advertised performance. In the mid-1980s, I clocked the Remington version of the 246 RN from a 6.5" BBL Model 24 Smith. My records indicate an average velocity of 669 fps. Recently, I checked five rounds of the Winchester Western 246 grain load from a Model 24 Heritage with the same barrel length, getting an average of 719fps. Several factors may explain the significant departure from factory specs. The original ballistic pendulum used to clock the black powder loads might have been a bit light in the loafers. The loads might have been extracted from a test barrel sans cylinder gap, or the load might have lost speed with the transition from black to smokeless propellant. In any case, it was not unusual for ammunition companies to post exaggerated velocity claims in the days before personal chronographs. For practical purposes, the generic .44 Special RN as advertised and in its actual factory performance may be expected to drive a bullet of substantial weight and calibration through the torso of a human adversary causing more or less immediate harm. It was a useful defensive round in the early 20th Century and, regardless of subsequent theories of stopping power, no doubt remains so today.

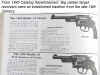

From a 1940 catalog advertisement

Actual velocities of factory loads from 6.5 & 4" barrels with hand loads approximating nominal performance.

|

Remington 246 RN |

Winchester 246 RN |

Lee 250 RN 4 Bullseye |

Keith 250 6 Unique |

|

6.5" BBL 669 fps |

6.5" 719 fps 4" 659fps |

6.5" 764fps 4" 745 |

6.5" 751 fps 4" 719 fps |

|

Spread 5 rounds 30fps |

50 fps 11 fps |

31 fps 27 fps |

47fps 45fps |

|

Energy Foot Pounds 245 |

282 fps 237 fps |

324fpe 308fpe |

313 fps 287 fps |

Factory level loadings of the .44 Special are accurate and, by virtue of minimal recoil and muzzle blast, pleasant to shoot. The bulk of my .44 shooting is done with loads of this approximate performance.

The Lyman Reloading Manual 47th Edition lists 6.9 grains of Unique as a factory duplicate load for bullets in the 250 grain range. I found that this loading with current components drove a Lee 250 grain round nose 943 fps from the 6.5" barrel and 829 fps from a 4" Model 29-2. I was able to closely approximate advertised factory performance with 4 grains of Bullseye with the round nosed bullet and 6 grains of Unique and a 250 grain Dry Creek Keith Design. Interestingly both of these powders have their origins in the late 19th Century and remain very suitable performers for the .44 Special. I regularly load 4.5 Bullseye under a 225 grain Round Nose Flat Point bullet. This averages about 830 fps and proved extremely accurate from the bench when I checked out the Heritage 24 with optical sights. Waggish shooters sometimes refer to Bullseye as "Flammable Dirt" but, residue aside, groups as well as velocity spreads are at least as small as those found with the factory cartridges.

Legacy of the Bulldog

Several "modern" .44 Special loads probably owe their existence to the small five shot revolvers popular for concealed carry. Most of the loadings employ bullets in the 180-200 grain range loaded to the standard pressures of 14,000 psi and below. A notable exception is the 165-grain Cor-Bon defense load that exits my 4" revolvers at just over 1200 fps. This is a +P level loading in the 20-29,000 psi range that brings the short .44s into serious contention with the best of the high velocity modern defensive auto-pistol loads. Recoil is mild and the Cor-Bon is completely controllable from the 4" Mountain Gun and other short N-Frames.

Current .44 Special Defense Loads from 6.5" Model 24 and 4" Barrel Model 29

|

Load |

Velocity Energy 6.5" |

Velocity/Energy 4" |

Spread 5 rounds 6.5&4" |

|

Cor-Bon 165 JHP |

1364 586 |

1205 532 |

---- ------ |

|

PMC 180 JHP |

901 325 |

863 320 |

72 23 |

|

Speer Gold Dot 200 |

872 338 |

833 308 |

32 65 |

|

WW 200 Silver tip |

782 272 |

743 245 |

26 23 |

|

Federal 200 Lead HP |

927 381 |

851 321 |

66 32 |

I recently got in a supply of these major .44 Special "Combat" loads and checked them out over the chronograph. I also fired several of each into dense, fat beef brisket to determine what expansion-if any-could be expected. The results were very encouraging. My stack of briskets measured between 7.5 and 8.5" thick. All of the loads penetrated this handily and were recovered from a telephone book placed behind. I alternated between a 4" Model 29-2 and a 4" Smith & Wesson Mountain Gun as both of these can be successfully concealed under most clothing. At the onset, I expected the lighter loadings of the .44 Special to return un-expanded bullets. As it developed, the ammunition companies have done their research and results with key loads were most gratifying.

The Winchester-Western Silvertip coasting along at a sedate 743 fps, expanded to approximately 75 caliber in a consistent manner. The same is true of the Speer Gold Dot 200 grain loading. Moving faster at 833 fps, the Dots expanded to a picture perfect mushroom measuring .75" and retaining the jackets in the same manner as the silvertips.

The Federal Lead Hollow Point 200 grain SWC recorded an energetic 851 fps average with bullets recovered at 70 caliber and above. The 180- Grain PMC old-tech jacketed hollow point expanded not at all but recorded a velocity of 863 fps.

The atomic Cor-Bon 165-grain load clocked 1205 fps and the bullets were an exploded mess after traveling through 7.5" of dense meat. The first 3" layer of brisket showed exit holes of 1" to 1.4" with the second and third layers containing jacket slivers. A substantial portion of cores and jacket bases were recovered from the telephone book behind the beef flesh.

Recoil from all of the above loads, Cor-Bon included, is quite mild and conductive to fine, multiple shot placement. Many shooters choose to carry the mid frame .44s available from Taurus and S&W over the small framed .357 snubs. From the performance of these loads, it appears that these shooters know what they are about.

Brevet Magnum

In the late 1920s, Elmer Keith loaded 250 grain bullets of his design over 18.5 grains of 2400 in the old folded head cases reducing the charge one grain for the newer solid head versions. He was cautionary in publishing these loads, saying that they were safe as loaded by him and in his guns but he would not guarantee them as loaded by anybody else. For a time, these loads were listed in several hand loading manuals one of which has lately become known as "The Blow Up Manual". The publisher of this manual survives and according to the scholarly "Rod WMG" would like to wave a magic wand and make all copies of this work disappear. For a time gun writers promoted the old .44 Specials as being lighter and more user-friendly than the newer .44 Magnums and inevitably published their results with loads similar to this. The load would crop up in relation to older Specials and the limited issue .44 specials put out at the urgings of said gun writers. It is probably an ok load in converted Ruger Blackhawks and is unlikely to cause catastrophic failure in the modern Specials. I have seen early N-Frames with blown locking bolt cuts and jugged forcing cones from attempts at duplicating this load. It is an unnecessary exercise in brinkmanship which is why I have not tried it in my .44 Specials.

Another traditional hand loading of the Special devolves around the classic Keith bullet over 7.5 grains of Unique. Skeeter Skelton promoted this one as an ideal law enforcement/light game load for the Smith Model 24 and other N-frame .44 Specials. My 6.5" Model 24 recently recorded velocities of about 1,000 fps with the Dry Creek / Ballisticast Keith bullet sized to .430". Switching to a cast 235-grain Lyman version of the Keith Hollow Point sized .429, I recorded velocities of 953 from the Model 24 and 833 from a 4" Model 29-2. Both velocities were beneath the threshold of expansion for the bullets cast from chilled shot metal. The noses had begun to flow but nothing like classic mushroom performance took place.

The 7.5 Unique load does not over-strain the modern .44 Special and would have some utility as a game load on smaller deer and animals of similar size.

All in all, the .44 Special remains a fine load for the shooter who enjoys putting large caliber bullets in close proximity one to another. It is also a confidence building anti-personnel round for the armed citizen who prefers the revolver.

since the website crashed AUG 2003, original publish date was 09 Dec 2002